Ancient Lycia stretches from Ekincik to Antalya, a mountainous, fiercely independent region whose dramatic landscape shaped its people, beliefs and enduring sense of identity.

Ancient Lycia runs from Ekincik to as far as Antalya, a semi-circle of some of the most mountainous and wild landscape in Turkey. High ridges to west and east, with peaks rising well over 3,000 metres, separated Lycia from neighbouring regions. A rugged plateau to the north cut it off from central Anatolia, while mountain ranges dropped precipitously into the sea along the coast.

During the Ottoman period it was called Uc, meaning "the Frontier", a name that captures the character of the region. Even into early summer, the highest peaks, including Akdağ and Bey Dağı, can remain snow-covered on their upper slopes.

As the landscape was wild, so too were the men who lived here. The Lycians were renowned for defending their freedom at all costs. In 546 BC the Persians defeated Croesus and advanced upon Lycia. On the plain of Xanthos, the Lycians met a much superior force, fought with gallantry, and were eventually forced back within their walls.

Five hundred years later in 42 BC, during Brutus' siege of Xanthos, the story is said to have repeated itself. Such was the Lycian attachment to independence that Lycia was among the last regions to be incorporated into the Roman provinces in Asia Minor.

In this remote region the sites of over forty cities have been identified. The most striking legacy is the tombs and sarcophagi carved into cliffs and hillsides. Ancestor worship appears to have been central, with elaborate tombs, inscriptions and curses against those who would tamper with the dead.

Five distinct types of tomb are often referenced: pillar-tombs, temple-tombs, house-tombs, pigeon-hole tombs and sarcophagi. Even today, it is difficult not to think of parts of Lycia as a vast necropolis, peopled with the shadowy figures of nobles and warriors.

Kalamaki, as Kalkan was known historically, is thought to have been founded 150 to 200 years ago by traders from the Greek island of Meis, which lies just offshore from Kaş. The harbour, long the only safe haven between Fethiye and Kaş, encouraged settlement from both Greek and Turkish communities.

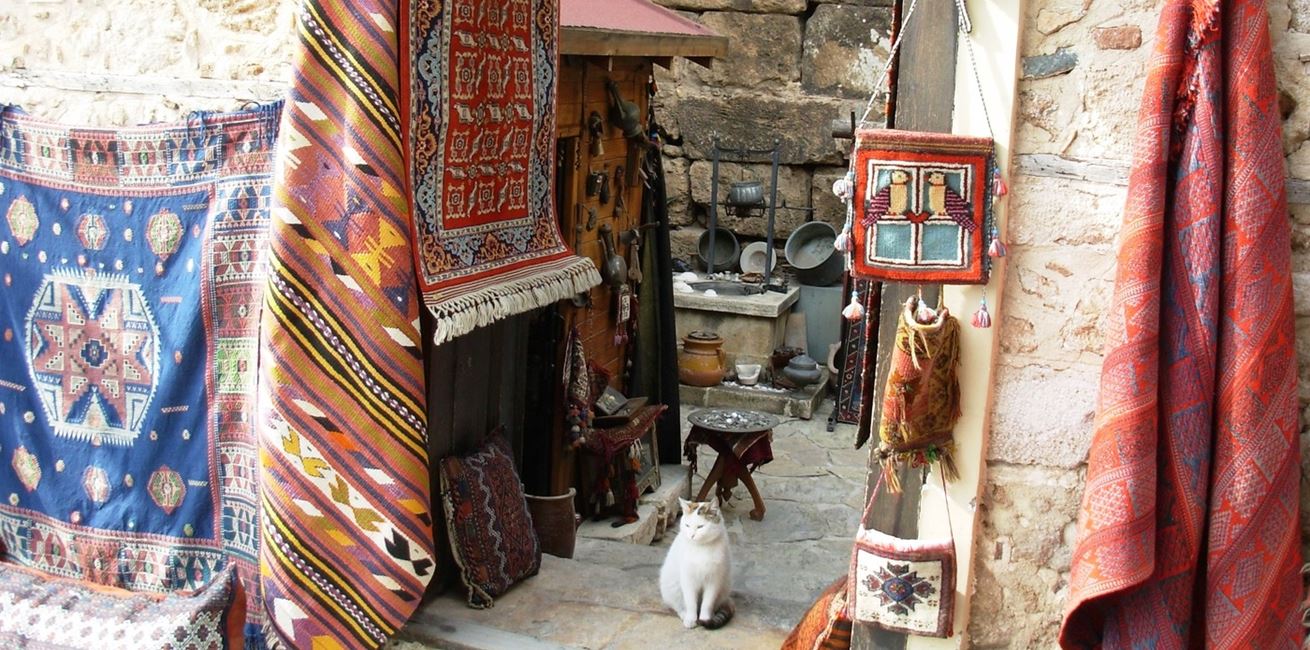

Much of Kalkan's early life was shaped by trade. Produce such as charcoal, silk, cotton, olive oil, timber, grapes and sesame travelled by camel from the plains and mountains, then left by ship for ports across the wider Ottoman world.

In the mid-20th century, population exchanges and changing opportunities drew many people away. Later, the completion of coastal roads, improvements to access, and the growth of tourism helped drive Kalkan's modern resurgence.

The Lycian shoreline, with its coves and islands, was long associated with maritime raiders. Campaigns to curb piracy were mounted from antiquity through to the modern period, with the coastline repeatedly returning to its old reputation when power shifted.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Lycia overview

- UNESCO World Heritage List (Turkey entries)

- UK Foreign Travel Advice, Turkey

- Türkiye Travel, Lycian Way

Note: Historical accounts vary across sources. If you are planning a walk or day trip, we can point you towards trusted local guides and current route advice.